TIDES at the University of Puerto Rico–HumacaoĪt the national level, Hispanic women continue to constitute only a small fraction of women who earn baccalaureate degrees in the computer sciences (figure 2). Each of these institutions has taken a bold and innovative step not only toward improving the learning outcomes and retention rates of women and women of color in computer and information sciences, but also toward ensuring that inclusive excellence, as it relates to all underrepresented groups in STEM, becomes an inherent part of institutional purpose and practice. Two examples include the University of Puerto Rico–Humacao, a Hispanic-Serving Institution (HSI) and Bryn Mawr College, a women’s liberal arts college. Since its launch, TIDES has supported nineteen institutions-including public and private institutions, minority serving institutions, liberal arts colleges, community colleges, research universities, and a women’s college-as they develop campus-level efforts aimed at empowering STEM faculty to implement culturally competent pedagogies. TIDES recognizes and directly addresses the limitations of current undergraduate STEM reform efforts by increasing the capacity of STEM faculty to positively affect underrepresented STEM students’ interest, competencies, and retention in the computer sciences and related STEM disciplines. Helmsley Charitable Trust, launched its TIDES (Teaching to Increase Diversity and Equity in STEM) initiative in 2014. To address these issues, the Association of American Colleges and Universities, with generous funding from the Leona M.

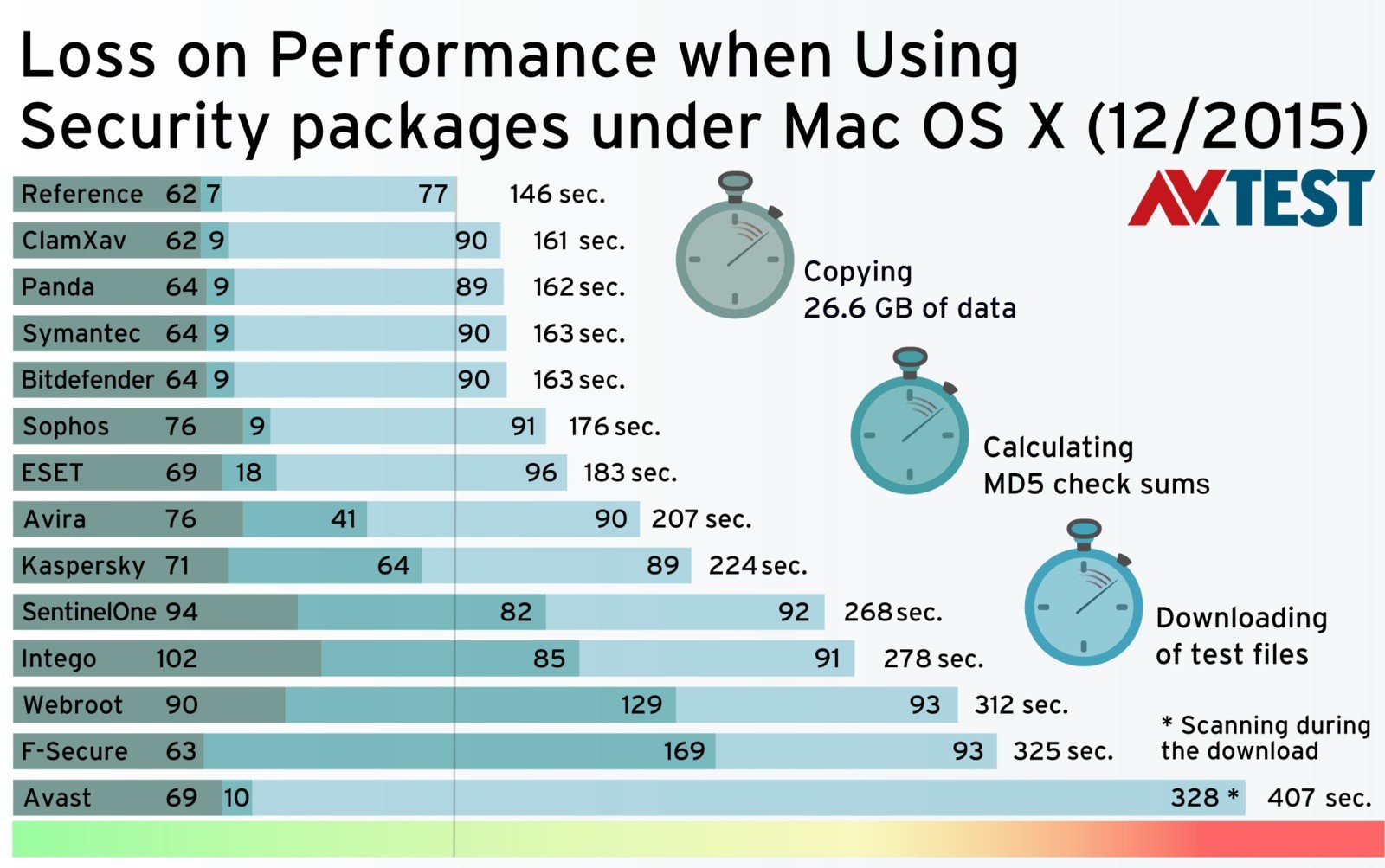

Mac for college 2015 professional#

Additionally, professional development interventions are often devoid of the elements necessary to achieve sustained change in STEM teaching patterns. Furthermore, many professional development opportunities aimed at helping STEM faculty enhance their teaching practices overlook the role of cultural competence in teaching and learning and fail to inextricably combine cultural sensitivity with advanced pedagogies. While overcoming stereotypes is an important strategy toward increasing women’s representation in the computer and information sciences, the most promising approach is pedagogical reform (Tsui 2007) that is not only evidence based, but also culturally sensitive.ĭespite the importance of such reform, STEM faculty often lack formal training in pedagogy and research-based learning theories (Vergara et al.

The relative absence of historical accounts of women as “human computers” in the early 1800s has led to masculinization of the discipline, devaluation of women’s contributions, underestimation of women’s mathematical aptitude and, ultimately, gender inequity. In the same period, the percentage of black, Hispanic/Latina, and Native American women who earned baccalaureate computer science degrees declined from 7 percent to a mere 5 percent (NSF 2015). Between 20, the percentage of baccalaureate computer science degrees earned by women declined from 28 percent to 18 percent (NSF 2015). While women of color and white women together represent the largest college-going segment of our society (NSF 2015), they remain a largely untapped-yet rich-source of talent in disciplines like computer science. Key to sustaining US global competitiveness is the country’s ability to harness the kinds of diverse perspectives that not only are known to fuel better scientific outcomes, but also are associated with the inclusion of underrepresented groups, particularly women and women of color (Cantor et al.

However, while the number of computer science baccalaureates has increased in recent years (NSF 2015), it continues to lag behind workforce demands in these disciplines (see figure 1), jeopardizing our nation’s capacity to remain at the leading edge of innovation. According to Evans, McKenna, and Schulte (2013), “by the end of the decade, the US economy will annually create 120,000 new jobs requiring a bachelor’s degree in computer science” to meet the demands of emerging fields like cloud architecture, forensic investigation, and geospatial technology. Undeniably, professions in science, technology, engineering, and mathematics (STEM) are among the fastest growing occupations in the US economy.

0 kommentar(er)

0 kommentar(er)